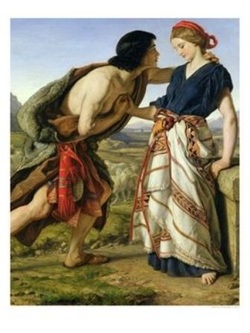

Though this is love at first sight, its consumation is vastly delayed. Jacob has to work 7 years for his deceptive Uncle Lavan before he is able to finally marry Rachel. A strenuous exercise in delayed gratification. And yet, their love is so great that the text tells us that the 7 years were but a few days for Jacob. Because of this morphing of time he was able to withstand the waiting period. And his commitment becomes a model for a love that transcends time and space.

Indeed, this sense of time transcendance takes us back to the moment of Jacob's weeping at the well. For the Midrash shares that Jacob wept because he saw with prophetic foreknowledge that he and Rachel would not be buried together.1 In this week's parsha we see his premonition fulfilled. Rachel tragically dies in childbirth and is buried “along the road to Efrat” as opposed to in the family burial site. At that moment of the kiss, the bonds of time were trancended and he was able to have a prophetic vision of the future.

Granted, it is a painful vision. But its not unlike the story of Rabbi Akiva who laughed when he beheld the tragic destruction of the Second Temple.2 He laughed because he realized that if the negative prophecy of destruction came true, then that would necessarily mean that all the positive prophecies of return and rebuilding would also come true for the Jewish people.

Indeed, we in our own days have had the enormous gift of witnessing the fulfillment, partial thought it may be, of the myriad prophecies of return to the Land of Israel.

We are the living recipients of that prophetic fruit.

In the poem below Rachel weeps for the fulfillment of the prophecy of her children's return to this land. She reminds us that just as Jacob love for her transcended time and allowed him to make it through those 14 years of work, so too if we beleagered builders of Jerusalem can but access the vastness of our love for this land, then we can also weather through whatever waiting periods time may hold. May we merit to witness the fulfillment of a true and enduring peace in this holy land.

"The Wait"

You wept

As wet as wells

Having spilled

The crowning ton of stone

Onto the sand

With withered hands

but high romance

Made the skinny shepards

call the place

- the wailing well -

for generations to come

And seven years

grown old

between your gaze and mine

- was like a day -

held between the gates

of withered hands

and weathered

wait

And know that

I weep as well

when memories of

the future spill

into our tent

and premonitions

limp into our

lamp-lit den

For if this ominous prophecy

must be then promise me

to plant your stones

on that baneful road

where house my bones

And let memorial stand,

a somber marker

in a severed land

To mark the promise

of prophecy

of transcendance

of time and of distance

with a mother's mad insistence

that the exile of her children

must end

And when finally march

our children by

from their battered walk

through genocide

I will be weeping3

loud with pleading

at that cornerside

- where Jerusalem

meets Gush Etzion

with her border guards

and building zones

And I will lament with rage

the historic parade

through Europe, Arabia

Aushchwitz, Asyria

and back to my grave

at Bethlehem's

barricades

And with the force of my weeping

and the form of your rocks4

will our children return

to the road to Efrat

And nineteen hundred years

- will be like a day -

held between the gates

of withered hands

and our children's

will to weather

the wait.

Endnotes:

1 Bereshit Rabbah 70:11

2 Talmud Makkot 24B

3 Foreseeing that the Jews on the way to exile would pass by the site, the Patriarch Yaacov buried her on the road on the way to Ephrath and not within the city so that she would sense their anguish and pray for them (Bereishit Rabbah 82:10). Add to this the quote from Jeremiah, “A voice is heard in Ramah, lamentation, and bitter weeping, Rachel weeping for her children; she refuseth to be comforted for her children, because they are not.” (Jeremiah 31:15) Thus, Rachel stands as the archetype for the mother weeping for her children.

4 It is interesting to note that Jacob in both of these stories is engaged in the moving of rocks. First he makes a stone altar (a matzava) at the site of his famous dream of the ladder. Then he moves the massive stone from atop the well for Rachel. And finally, in the story of her death, he again creates a matzeva, a stone memorial, upon Rachel's roadside grave.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed